250/330 GT SWB and 500 SF Telaio (Frame)

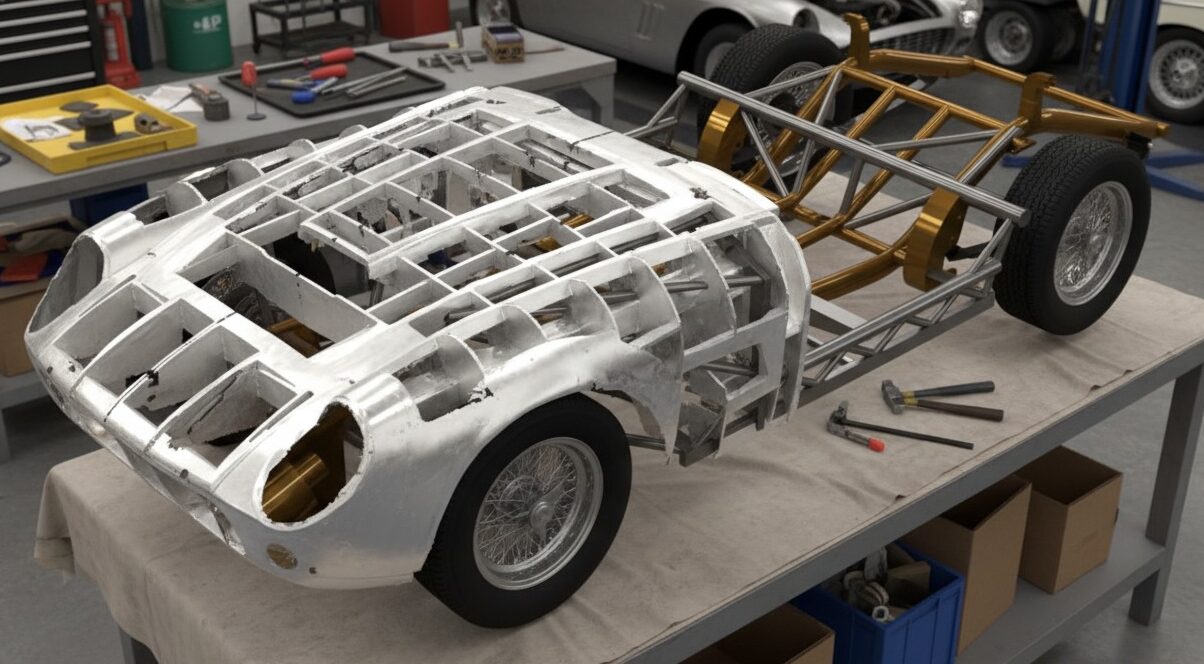

The 250 GT series used a tubular steel chassis that balanced light weight with rigidity and it became the backbone for multiple celebrated variants including the short wheelbase Berlinetta, the Lusso and the race focused GTO. The design offered tight handling strong braking stability and a platform that coach builders could shape into elegant bodies while keeping race grade performance in view.

Chassis Design: Innovation Meets Performance

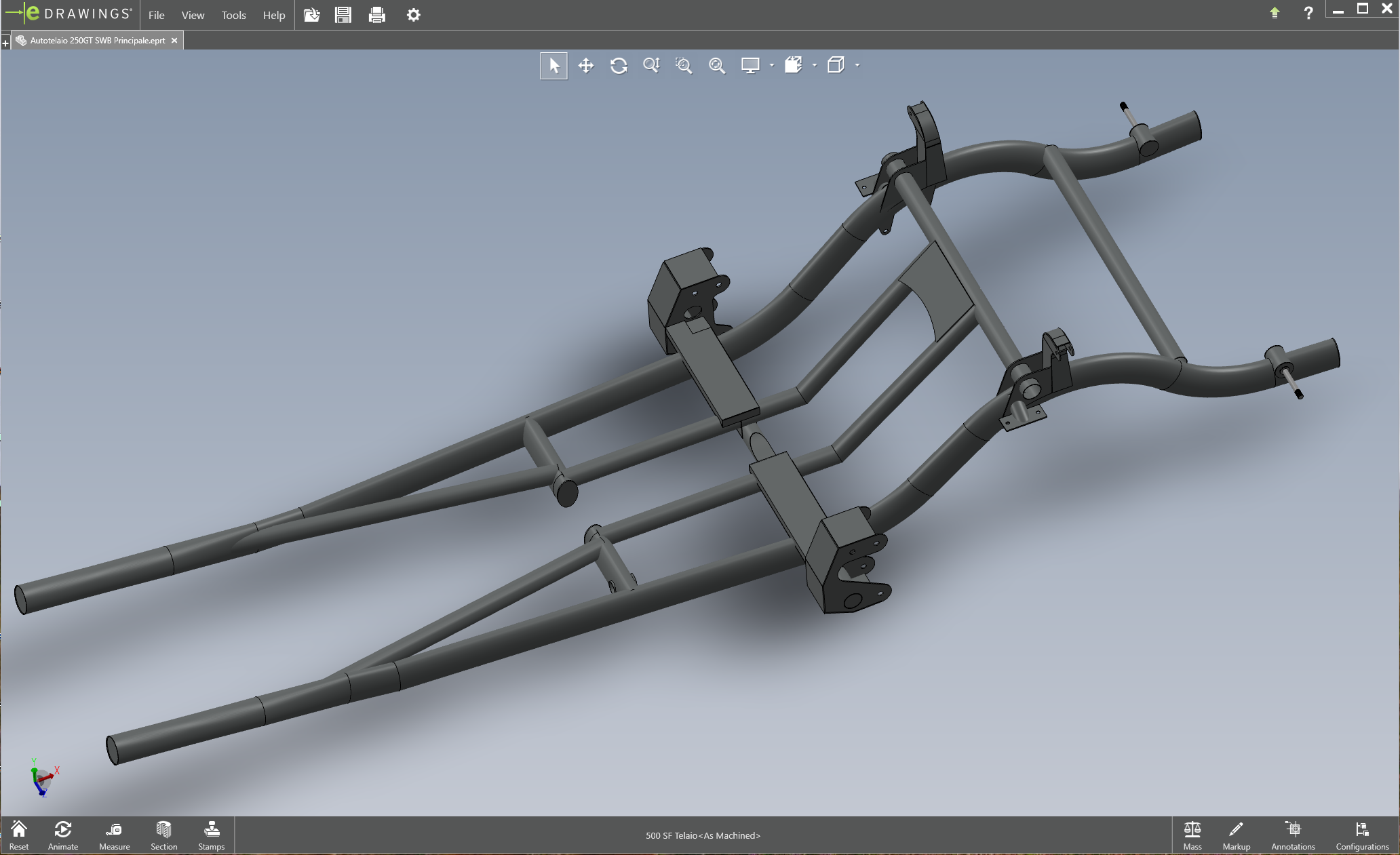

The frame used interlaced tubular members arranged for high rigidity with strategic bracing around the engine bay the suspension pick up points and the rear section. In short wheelbase form the 2,400 millimeter wheelbase sharpened turn in and improved agility which is why privateers and works supported teams favored it for endurance events. Over time development pushed the layout toward a true space frame with a higher count of small diameter braces that further increased torsional stiffness and steering precision.

The Roar of a V12!

Across the line a 3.0 liter Colombo V12 provided smooth power delivery and high rev capability. In competition focused builds output in period was commonly quoted in the range of 280 to 300 horsepower with top speeds beyond 150 miles per hour when gearing and bodywork allowed. The combination of low mass a stiff frame and a free revving V12 created a road car that could credibly compete at major circuits while remaining usable on public roads.

History and racing impact

The 250 GT family bridged glamour and competition. Bodies styled by Pininfarina and built by Scaglietti sat over frames that were ready for serious use at Le Mans, Nurburgring and Sebring. Later the GTO evolved from the short wheelbase Berlinetta underpinnings and delivered a run of GT championships that cemented the legend of the 250 series. While Enzo Ferrari did not personally drive in these events during this era the cars carrying his vision became benchmarks for grand touring competition and for performance road machinery.

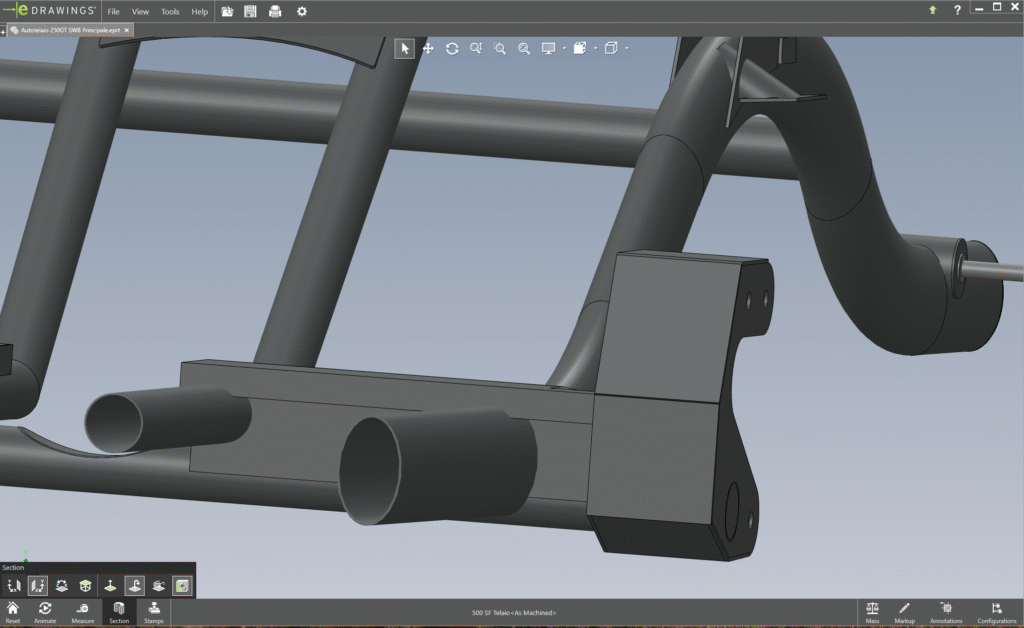

Innovation through the simplicity of an Oval tube

A key structural advance was the adoption in period of large section oval main rails measured at about 55 millimeters by 92 millimeters derived by flattening 75 millimeter and 76.2mm tubing (more on this interesting fact below). Moving from round to oval sections increased the second moment of area about the vertical axis which raised bending stiffness in the plane that matters most for cornering and braking loads. The broader section also improved local attachment stiffness at suspension pick up points while the network of smaller braces preserved torsional integrity. In practice that meant crisper response through initial turn in more stable transient behavior over curbs and better consistency in long stints as the chassis resisted flex that can upset alignment under heavy load. Period references also note variations such as 80 millimeter and 90 millimeter oval sections on certain competition and road examples which points to ongoing tuning of stiffness and weight to suit event demands and bodywork.

Speed and Elegance

The 250 GT chassis showed how careful section choice and bracing strategy could deliver race level control without sacrificing elegance or usability. That blueprint informed later icons and it remains a touchstone for collectors and engineers who study how a light rigid frame paired with a responsive V12 creates a driving experience that still feels special today.

| Element | Significance |

|---|---|

| Chassis Design | A lightweight, rigid tubular framework enabling both performance and coachbuilt flexibility. |

| Historical Role | Anchor for variants spanning from refined grand tourers (Lusso, Coupé) to racing legends (SWB, GTO). |

| Racing Legacy | Led Ferrari to GT dominance; the GTO’s championships and the SWB’s dynamic prowess are still celebrated today. |

USA Steel Used In European Racing After WWII

In the immediate postwar years many small Italian constructors turned to tubular steel frames to build their competition cars. Quite a few of these frames were made using inch sized tubing rather than metric. This was not a matter of preference but of practicality. After the war large quantities of surplus aircraft material flooded Europe. Chrome molybdenum tubing, alloy sheet, and other components originally manufactured for Allied aircraft were sold cheaply and were readily available. Because much of that stock came from American and British suppliers, it was dimensioned in inches rather than millimeters. Italian workshops eager to restart production and enter racing simply used what they could source locally, meaning many of their first frames were literally measured in inches.

Gilco and Early Frame Builders

One of the most important suppliers of these frames was Gilco founded by Gilberto Colombo (not related to Gioacchino Colombo, creator of the Ferrari V12 engine), a Milan based specialist in tubular steel construction. Gilco built frames for early sports cars and single seaters used by companies around Modena. Their jig work and welding experience allowed small constructors to obtain light yet stiff chassis at a time when few had the resources to engineer frames from scratch. Gilco’s tubes were often inch sized aircraft surplus, and this practice influenced the design of the first generations of postwar Italian race cars.

Early cars carrying Enzo’s badge also used Gilco frames before the company brought more work in house at Maranello. Maserati, meanwhile, relied on similar techniques, and small workshops across northern Italy produced special one offs using whatever tubing they could acquire. Even Scuderia Lancia experimented with tubular concepts in the same period, again often with leftover inch stock.

Why Modena Became a Racing Hotbed

Modena and nearby towns already had a strong tradition in precision metalwork. During the war, many craftsmen had honed their skills producing aircraft components. When peace returned, the same talents were redirected to cars. The region’s network of twisting country roads, combined with access to the small Autodromo di Modena, gave constructors a natural test track.

The area also concentrated extraordinary personalities. Enzo began operations in Modena before moving production to Maranello just a short distance away. Maserati was based in the same area, and a host of body shops and machine shops clustered nearby. The culture of speed, fueled by national events like the Mille Miglia and Targa Florio, meant there was demand as well as enthusiasm. In this environment, surplus inch tubing became the raw material of an industry that would soon dominate international racing.

Legacy

The widespread use of US made aircraft tubing in early Italian racing frames shows how global events shaped the foundations of the motorsport industry. Local specialists like Gilco turned wartime materials into peacetime innovations, and the Modena area’s mix of skilled labor, passion, and infrastructure gave rise to an ecosystem that still defines the heart of Italian performance engineering today.

Tech Specs: Gilco Tubular Frames

Main Tubes: Surplus aircraft steel, often inch-based sizes (e.g. 2.5 in, 3 in round)

Material: Chrome-molybdenum alloy, lightweight yet high tensile strength

Cross Sections: Round tubes in early frames; later evolved to oval sections

Key Innovation: 55 × 92 mm oval tubing (derived by flattening 75mm and 76.2mm round stock)